New York February 9, 2018: A Call to Action and an Opening

By Barbara Hoffman

January 24, 2018 was an intense, immersive and inspiring day: an existential linking of 13TH by Ava DuVernay, best known for her 2014 Best Picture nominated Martin Luther King drama Selma, at the New York State Bar Association Annual Meeting, and the opening of Derrick Adams’ Sanctuary at the Museum of Arts and Design. The State Bar Meeting is a good source for mandatory CLE credits and the morning session I attended was informative and useful, dealing with current issues in estate planning after the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and an insightful and humorous presentation on the wills of the rich and famous with the ten pitfalls to avoid. This entry, however, is not about advising artists on the estate planning and the preservation of a legacy. For information on artists estates, see /Publications/A-Visual-Artists-Guide-to-Estate-Planning-The-Marie-Walsh-Sharpe-Art-Foundation-and-The-Judith-Rothschild-Foundation.pdf

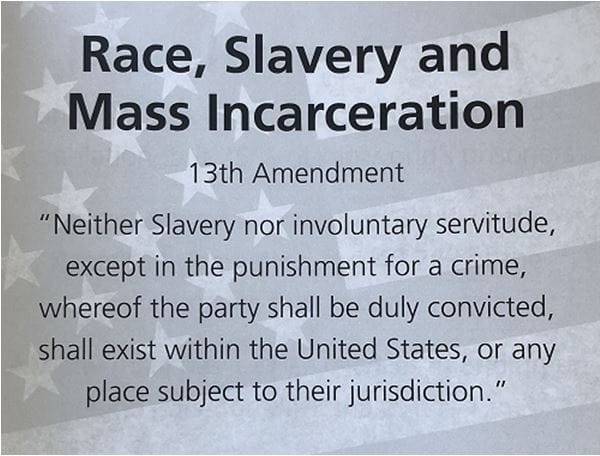

In the afternoon, I attended the Presidential Summit: Race, Slavery and Mass Incarceration, hosted by Sharon Stern Gerstman, President of the New York State Bar Association. The Summit featured 13TH, its title drawn from the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. DuVernay has stated her interest in the topic was visceral before intellectual: police officers were symbols of fear rather than safety.

Slide 1 from the New York State Bar Association Presidential Summit

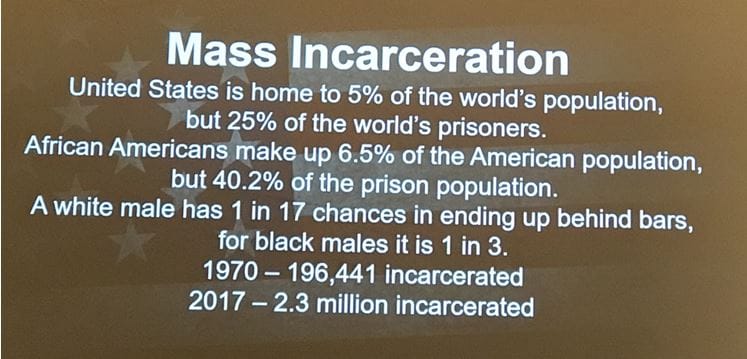

When the 13th Amendment was ratified into law on December 6, 1865, it abolished slavery, with one key caveat: “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” More than 150 years later, that exception has proven much more than a mere footnote to history. More African-American men are incarcerated, or on probation or parole, than were enslaved in 1850, and the United States, which accounts for 5% of the world’s population, counts nearly a quarter of the world’s incarcerated people. According to the American Bar Foundation, half of those imprisoned are parents. There are about 3 million children in the United States with an incarcerated parent or a parent who has recently been released.

According to John Hagan, co-director of the ABF Center on Law and Globalization, mass incarceration has had a significant impact on the needs and rights of children of those behind bars as well as the communities where they reside. He notes that two thirds of incarcerated women are mothers.

According to the American Bar Association, “reach of the criminal justice system extends even farther. For every person in prison, America has two more people on parole, probation, or some related form of control. In actual numbers, that means that the U.S. has a total of more than 7 million people behind bars or subject to some kind of control that can land them behind bars. That is larger than the combined populations of Los Angeles and Chicago. If everyone in jail lived in one city, it would be the second largest metropolis in America, one of the many insights in Ernest Drucker’s book A Plague of Prisons: The Epidemiology of Mass Incarceration in America.”

Slide 2 from the New York State Bar Association Presidential Summit

Premised as a historical survey that maps the genetic link between slavery and today’s prison-industrial complex, 13TH begins with the depiction of black men as a threat to white women in the Birth of a Nation in 1917.

Juleyka Lantigua-Williams’ commentary in the Atlantic (Oct. 6, 2016) observed, ” 13th explodes the ‘mythology of black criminality’ as The New Yorker‘s Jelani Cobb at one point in the film refers to the successive and successful measures undertaken by political authorities to disempower African Americans over the last three centuries. The academic and civil-rights advocate Michelle Alexander, author of the 2010 book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Color blindness unpacks how the rhetorical war started by Richard Nixon and continued by Ronald Reagan escalated into a literal war, a ‘nearly genocidal’ one. The Southern Strategy is unmasked as a political calculation that decimated black neighborhoods but won the southern white vote.”

Other politicians in the film do not fare better: George H. W. Bush and his campaign attack against Michael Dukakis’s furlough program involving Willie Horton, Nixon’s “War on Crime”, the thinly veiled racial appeals of President Reagan’s Southern Strategy and his “War on Drugs”, Bill Clinton’s “Three Strikes and You’re Out” Crime Bill and Welfare Reform Initiatives, and Hillary Clinton’s response to the perception that the Clinton Administration was “soft on crime”, including her 1996 remark on “super predators”.

Throughout the film’s trajectory, a single word flashes in giant white letters on a black background: CRIMINAL. Is it a condemnation of past deeds or an accusation aimed at everyone who is complicit?

13TH confronts the nexus between mass incarceration, the prison-industrial complex, poverty and the U.S. criminal justice system. At the same time that financial incentives encourage arbitrary, prolonged and unnecessary incarceration, the inability to pay fines and fees, made evident when the killing of Mike Brown exposed Ferguson’s criminal justice system, causes individuals to be incarcerated not for the underlying offense but for the inability to pay a fine.

Poverty, not crime, caused the unforgivable death of Kaleif Browder, a young man arrested in 2010 at age sixteen in the Bronx for a crime he didn’t commit. Early in the morning on Saturday, May 15, 2010, Kalief Browder and a friend were returning home from a night out at a party in the Bronx. While en route, the young men were stopped, searched, and subsequently arrested by police officers on suspicion of theft. Originally, police told the two teens they were just reported as having stolen a backpack. Minutes later, the teens were told that the alleged victim in question was actually robbed two weeks prior. With unimaginable strength of character and courage, Browder refused to “plea bargain” to a lesser offense, and maintained his innocence. Browder spent more than one thousand days on Riker’s Island awaiting trial because his mother could not afford to pay his bail, set at $3,000. Ultimately, with no evidence that he had committed a crime, he was released. Two years alter, paranoid and mentally injured from the beatings and bouts of solitary confinement at Riker’s Island, Browder committed suicide. In 2016, Mayor Bill De Blasio banned solitary confinement in New York City for those 21 and younger.

Shocked by the enormity of the problem, I sensed a collective sense of despair in the audience. Fortunately, the forthright exchange of the distinguished panel, comprised of Hon. Darcel D. Clark, Bronx County District Attorney and the first African American woman to hold that post in the U.S., Chanta Parker, Esq., The Innocence Project, New York, NY, Jeffery P. Robinson, Esq., American Civil Liberties Union, New York, NY, and moderated by Hilarie Bass, Esq., President, American Bar Association, shed a beacon of hope that we as attorneys could act for change.

The breadth of experience among the panelists provided a range of reactions to the issues of race, criminal justice and history raised by the film. Parker noted that half of the black women in America have an incarcerated loved one and that African Americans in poor communities are presumed guilty until proven innocent. She pointed out throughout the hour-long discussion that the damage done by incarceration extends beyond the individuals behind bars. Robinson stated “I’m angry because none of this is new.” For him, the criminal justice reforms being discussed, including bail and imprisonment for failure to pay fines and fees, will amount to so much “tinkering” if the fundamental truth is not addressed about how today’s criminal justice system came to be and if we fail to acknowledge that we are a nation founded on the belief in white supremacy. Robinson alluded to the fact that the Emancipation Proclamation had provided compensation to slave owners, a fact I had not previously heard and which led me to further research.

From an interview with Jon Booth, a PhD student in history at Harvard working on race and criminalization after emancipation for the article Were US Slave Owners Really Paid $300 Per Slave? at OrchestratedPulse.com:

Did slave owners really receive $300 per slave?

Yes, but very few. In 1862 the federal government abolished slavery in Washington DC, but set up a commission to compensate slaveholders who did not join the Confederacy. In the end the government paid out an average of $300 per slave to the 979 owners of 2,989 slaves. Those 2,989 slaves represent approximately 0.075% of the 4 million slaves in the country at the time. Though many abolitionists objected on principle to any action which implied that human beings could be bought or sold, the abolition of slavery in Washington, DC created an island of freedom in between the slave states of Maryland and Virginia and became a magnet for runaways from the region. What is more, the Emancipation Act forbade slave owners from evading the act by removing slaves from the District and successfully enforced this prohibition.

The Lincoln administration attempted to pursue a compensated emancipation policy in the Border States, but gave up after the Delaware legislature bluntly rejected his offer. Thus, no other American slave owner was ever compensated… The National Archives provides a brief, yet detailed, review of the DC Emancipation Act and its impact. Surprisingly, in addition to this legislation, Congress also passed a supplemental act that allowed slaves to come to DC and petition for their own freedom. History is complex.

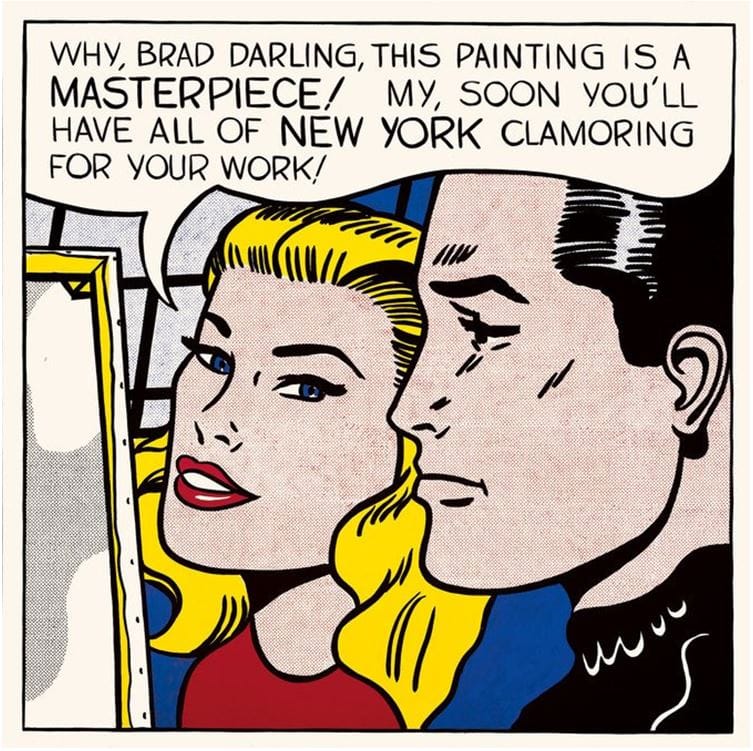

Roy Lichtenstein’s “Masterpiece” (1962). Courtesy of the Estate of Roy Lichtenstein.

It is not surprising that Agnes Gund, the well known philanthropist, art collector and patron, former president of MoMA and current chair of MoMA PS1, was moved to action in January 2017 to sell Roy Lichtenstein’s 1962 “Masterpiece” hanging above her fireplace for $165 million including fees after being inspired by Alexander’s book and DuVernay’s documentary. The purpose, to create a fund that supports criminal justice reform and seeks to reduce mass incarceration in the United States. The Art for Justice Fund, jointly administered with the Ford Foundation, began with $100 million from the proceeds of the Lichtenstein and has already received contributions from other art collectors.

Those who have already committed to the fund – and are being called founding donors – include Laurie M. Tisch, a chairwoman of the Whitney Museum of American Art; Kenneth I. Chenault, chief executive of American Express, and his wife, Kathryn; the philanthropist Jo Carole Lauder; the financier Daniel S. Loeb; and Brooke Neidich, a Whitney trustee.

The fund will make grants to organizations and leaders who already have a track record in criminal justice reform – like the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Ala. – that seek to safely reduce jail and prison populations across the country and to strengthen education and employment opportunities for former inmates. The fund will also support art-related programs on mass incarceration.

As Ron Kammer, chair of the ABA Litigation Section stated in 2012: “As a nation, we have become addicted to incarceration. We have convinced ourselves that the best way to control any kind of behavior is to criminalize it. And if that doesn’t work, we will increase the penalties, and then increase them again. Like other addictions, this one is wreaking havoc on our lives. For more than a hundred years, America didn’t behave this way. In the mid-1970’s, we made some disastrous choices that have taken a terrible toll. What we have come to think of as normal is anything but.”

Derrick Adams: Sanctuary at the Museum of Arts and Design,

January 25, 2018 to August 12, 2018

For transparency and full disclosure, I am a longtime follower and a friend of Mr. Adams and was privileged to contribute to the exhibition. Since about 2006, I have followed his amazing journey as a multidisciplinary artist exploring through video, performance, works on paper, painting and sculpture. Adams’ multi-layered, works reflect the complexity of the social, economic and political structure experienced by and African American artist.

Barbara Hoffman with Derrick Adams at his opening for Figures in the Urban Landscape, Nov. 8, 2017. In the background: “Figure in the Urban Landscape 3,” 2017, by Derrick Adams. Tilton Gallery, courtesy of author.

A cyclical narrative runs through Adams’ works, telling the story of someone who first entered the world knowing only pride and love for his heritage only to be confronted with a society which casts shame on this heritage. Adams examines the face of popular culture and the media on the perception and construction of self-image. The fragmentation and manipulation of structure and surface, formal arrangements of forms and space and a complexity of meanings recur throughout the exhibition. Adams’ prints and collages which feature simple shapes, bold color and contrast, and reflect not only a dialogue with art history, philosophy and contemporary art, but an engagement with autobiographical content and contemporary events remind me very much of the artist Robert Motherwell, the New York School painter. Just as key scenes of Motherwell’s work include a dialogue between European modernism and a new American vision, and between formal and emotional approaches to artmaking, Adams’ work engages contemporary art techniques and practice, the American modernist tradition and the vision of the African American experience as it encounters the social and political structure of its time. Nothing is obvious, as Adams with poetry and wit reclaims his identity.

When I asked Adams about a prior work that I found relevant to Sanctuary, he responded: “In my video work “Reality Bites: Storytime with That Cat Pat” a puppet I created reads an excerpt from Bell Hook’s chapter, Black Vernacular: Architecture as Cultural Practice, from her book Art On My Mind. In the chapter Hook’s writes of a lesson from a high school art class where she was asked to imagine the house of their dreams. She did not think any decisions she made were political and that all thought related to the project was rooted in imaginative fantasy. She made a list of all the things in a house she found compelling. In my video I juxtapose this narrative read by the puppet within a backdrop animating a rural forest landscape or wildernest scene occupied by a puma. The intention was to explore the diverse notions of environment and home as it relates to individuals.”

In the Huffington Post article A Conversation With Derrick Adams Dec. 6, 2017, Marcia G. Yerman writes that “Adams spoke incisively about an integral part of his rearing – what he identified as the requisite need to acquire a “double consciousness.” He explained the lesson he absorbed as a young boy. It was the knowledge that “black folks had of themselves,” and the alternate view. That was, “The world looks at you as a monster – the other.” Adams gave the analogy of a young, black male child “skipping and then running,” only to have that simple activity construed as flight from an illusory crime. The need for an ongoing “dual identity,” as a means of survival for the adult black male, is a theme that repeatedly manifests itself in Adams’s work. Explored is a representation of an outer appearance in conflict with the truth of an inner psychology. Adams sees the majority of his work “residing in the idea of how outside influences impact the perception of self.”

In the Bomb Magazine article Transforming the View: Derrick Adams Interviewed by Monica Uszerowicz Jan. 5, 2018, Uszerowicz asks: ‘In dealing with cultural representation, you’ve spoken about maintaining a double consciousness of yourself, as someone seen as an ‘other.'”

DA: I’m a black artist-and I’m also just an artist. I’m American and educated, but I come from Baltimore, an urban space with various socioeconomic groups of black people. For me, this work is much more complex than a television show, or something that can be condensed into an hour-long program. It’s about understanding the complexity of black people as much as people understand the various ranges of socioeconomic structures of white people-which is equally as contrasting.

“The Negro Travelers’ Green Book,” from the fall of 1956. Credit New York Public Library.

The immersive and stunning installation is inspired by “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” a series of AAA-like guides for black travelers published from 1936 through 1966 and published by postal worker Victor Hugo Green. It is not surprising that the guide coincides with the Great Migration.

Over the years, they were used by drivers who wanted to avoid the segregation of mass transit, job seekers relocating North during the Great Migration, newly drafted soldiers heading South to World War II army bases, traveling businessmen and vacationing families.

“While the Green Book reflected the disturbing reality of segregation of African Americans, it permitted them to travel the non-segregated roadways and to feel American,” the artist said.

Derrick Adams. Photo by Terrence Jennings. Courtesy of the Museum of Arts and Design

While growing up in Baltimore in the 1970s, he was visited frequently by relatives driving from Virginia or New York. “My great-aunts would wear these very particular pants outfits and driving gloves and little driving hats. It was very sporty, unlike the domestic look of the women in the house,” he recalled. “It was about travel culture, and it created in my mind a representation of liberation.”

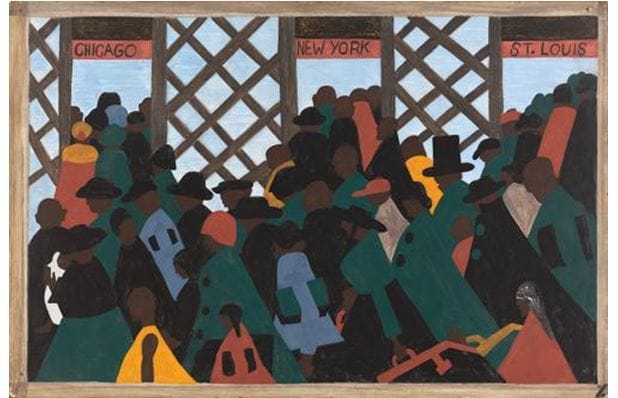

It comes as no surprise that Adams has acknowledged Jacob Lawrence as a major influence, describing the migration series as a powerful depiction of the mass movement of hat wearing, suitcase carrying African Americans relocating north for industrial jobs, educational opportunities and freedom- perhaps with a green book in the pocket.

Jacob Lawrence Panel 1: During World War I there was a great migration north by southern African Americans (1940-41) Courtesy of The Phillips Collection, Acquired 1942

Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series (1940-41), a sequence of 60 paintings, depicts the mass movement of African Americans from the rural South to the urban North between World War I and World War II-a development that had received little previous public attention.

The series was the subject of a solo show at the Downtown Gallery in Manhattan in 1941, making Lawrence the first black artist represented by a New York gallery. Interest in the series was intense. Ultimately, The Phillips Collection and New York’s Museum of Modern Art agreed to divide it, with the Phillips buying the odd-numbered paintings.

Photograph of Shannon Stratton, the Museum of Arts and Design’s Chief Curator and co-curator of the exhibition. Photograph by author, Jan. 24, 2018.

Dexter Wimberly, the executive director of Aljira, a center for contemporary art in Newark, organized the show with Shannon Stratton.

As Wimberly told me, “Curating Sanctuary allowed me to explore a little-known aspect of American history that had a tremendous impact on how we live today. I’m still shocked that I was not aware of The Green Book prior to organizing this exhibition. However, my research for the show revealed to me that it was an extremely important publication, that for many was literally a lifesaver. My mother and father were born in the rural south in the 1940’s and 50’s. The Green Book is a reminder of the world they grew up in and the courage it took to live a full life and to pursue the American Dream.”

Derrick Adams, You’ll Have Your Own View (2018) at the Museum of Arts and Design.

Photograph by author, Jan. 24, 2018.

Installation view of Sanctuary by Derrick Adams at the Museum of Arts and Design.

Photograph by author, Jan. 24, 2018.

The road that bisects MAD’s gallery space follows a path up, over and down the sides of free-standing wooden doors. Visitors must pass through them to traverse the road. “I’ve thought a lot about barriers, and accessibility, and obstacles, and perseverance,” explained Adams.

Barbara Hoffman, Performa Board Member and Counsel, with Performa friends Job Piston (left), special projects manager, and Charles Aubin, curator (right) at Derrick Adams’ Sanctuary at the Museum of Arts and Design. Photograph by Jenna Bascom, Jan. 24, 2018.

Adams states, “The project is really timely, considering all of the conversations and issues surrounding immigration and racial tension,” he said. “Things are happening that echo what the Green Books were trying to prevent. If anything, I want people to know how important it is to have freedom to go where you want to go.”

13TH and Sanctuary have in common the message that freedom is a struggle that requires our constant vigilance and understanding of the roots and underpinnings necessary for each of us to make the journey.

“You hear stories from older people about how far they had to drive to get gas or stop. Some would have to keep gas in their car when they traveled. And a pot in their trunk,” Adams said. “I’ve thought a lot about the freedom people must have felt from the Green Books, not worrying about where to stop and what’s going to be on the other side, pre-Yelp.”

As Meredith Mendelsohn writes for the New York Times article How an Artist Learned About Freedom From ‘The Negro Motorist Green Book’ Jan. 19, 2018: “altogether, the show is a highly visceral experience, channeling some of life’s more underappreciated privileges: the freedom to stop at a diner, or to insert a key into a humble motel doorknob after a long day of driving.”

A Beacon of Hope

Derrick Adams, Beacon (2017) at the Museum of Arts and Design. Photograph by author, Jan. 24, 2018.

Collectively, the road we are traveling is a difficult one with barriers along the route; however, efforts of the legal and artistic communities of which I am a part continue to resist and transcend these barriers.

I live in New York, a sanctuary city. On February 8, 2018, several hundred public defenders lined up outside a courthouse in the Bronx with posters that read “immigrants are welcome here” after ICE agents arrested Dembele Lanier, an illegal immigrant who was leaving the courthouse after seeing a judge for an assault charge. His wife said the ICE agents were waiting for Lanier outside of the courthouse, WNYC News reported.

Last month, Governor Cuomo announced that largely ending the use of cash bail in low level cases would be a centerpiece of his forthcoming criminal justice reform legislative package.

Justice Maria Rosa of the Dutchess County Supreme Court went even further in a decision on Monday, February 7, 2018. She ruled that setting cash bail on a defendant without considering his or her ability to make such a payment violates the constitutional right to due process and equal protection. She said that the earliest legislative action could occur would be 2019, leaving thousands of individuals imprisoned until that time. In addition, Judge Rosa pointed to incarceration statistics, writing that “across our state, between 60 percent on average, and in New York City as much as 75 percent, of inmates have not been convicted of a crime but are awaiting arraignment or trial.

The decision represents an important victory for the New York Civil Liberties Union. Judge Rosa stated, “It is clear to this court that a lack of consideration of a defendant’s ability to pay the bail being set at an arraignment is a violation of the equal protection and due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and of the New York State Constitution: Clearly, $5,000 bail to someone earning $10,000 per year, like the petitioner, without significant assets, is much more of an impediment to freedom than $5,000 bail would be to a defendant earning substantially more and/or with significant assets… Protection against discrimination is never more important than wen a person’s freedom is at stake. Since one accused of a crime in the United States is presumed innocent until proven guilty, the setting of bail is supposed to be limited to those defendants who are either a danger to a specific individual or to the public or who pose a flight risk.”

For information on upcoming events related to Derrick Adams: Sanctuary, see: http://madmuseum.org/exhibition/derrick-adams-sanctuary