The Art Lawyer’s Diary June 2023

The Hoffman Law Firm’s The Art Lawyer’s Diary by an art world insider is a guide to navigating the implications of current developments in art law as they relate to artists, collectors, galleries, and museums, as well as a forum for the discussion of the implications of current events at the intersection of art, law politics, and culture for the art world and beyond.

U.S. Supreme Court Restores Balance to Fair Use Doctrine by Rejecting the Appeal of the Andy Warhol Foundation in Warhol v. Goldsmith

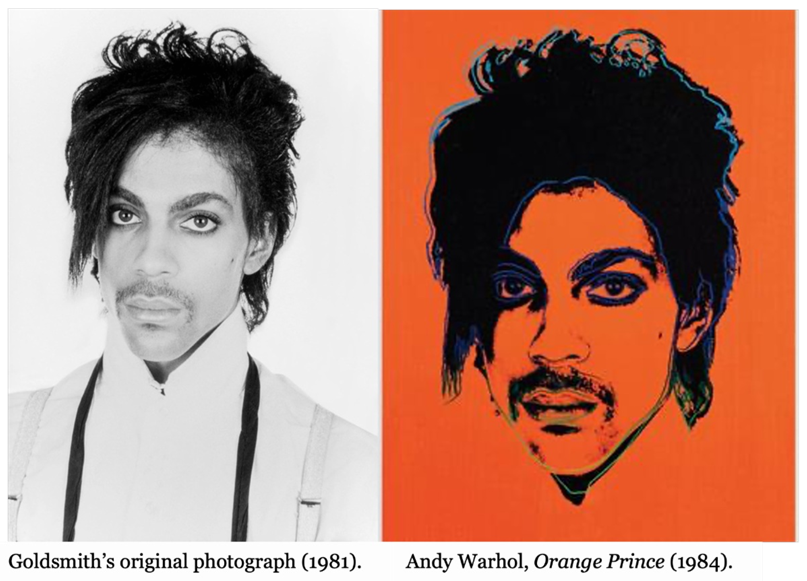

It should not be a surprise to my readers that I breathed a sigh of relief on May 18, 2023, upon learning that the Supreme Court had issued its anxiously awaited decision in the landmark case of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, ruling against the Warhol Foundation’s (AWF) claim of the right to license Goldsmith’s copyrighted portrait of the musician Prince without her permission, on the theory of fair use.

The Copyright Act of 1976 provides that the fair use of a copyrighted work is not an infringement of copyright if it is used for purposes including criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research.

The Supreme Court’s affirmation of the Second Circuit’s decision is a welcome correction to the importation of the “famous artist exception” argued by the AWF; that is, that appropriation artists get a free pass to use copyrighted material as facts of popular culture without commenting on the original work and without paying the customary price. To state it another way, the Court rejects the bright line rule argued by the AWF and its supporters (i.e., Amicus Curiae of Art Law Professors) that the fair use doctrine does not comport with the First Amendment if it does not permit the public to use facts, ideas, and expression itself, if it creates a new meaning and message as Warhol clearly did.

One Art Nation, for whom I write regularly, requested my commentary on the Supreme Court decision. The Art Lawyer’s Diary: Lots of Smoke and No Fire as Goldsmith Prevails Against Warhol Foundation in the Supreme Court provides an in-depth analysis and historic context for the decision.

This commentary adds a more personal note based on my involvement and success in litigating fair use cases on behalf of photojournalists and visual artists whose works have been used without permission on a theory of fair use.

The doctrine of fair use permits and requires courts to avoid rigid application of the copyright statute, when, on occasion, it would stifle the very creativity that the law is designed to foster. In determining whether a particular use is protected under the doctrine, courts are to apply an “equitable rule of reason” analysis, guided by these four factors:

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Although a court must weigh all the factors, the first — in particular, a use’s “transformativeness” — is most important, and “has a significant impact on the remainder of the analysis.”

“The more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use,” reads the 1994 Supreme Court opinion in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., the first to import the concept from a law review article by Pierre Leval published in 1990.

In a seven-to-two decision authored by Justice Sotomayor, the Supreme Court opined for the first time in 29 years on the fair use defense with respect to artistic expression, specifically to reaffirm and elaborate its prior precedent based on Campbell. The decision was a narrow one, to the extent that it did not even determine whether AWF infringed the copyright of Goldsmith’s work. The Court limited its decision to whether Warhol’s specific use of Goldsmith’s photograph was “transformative.” The Court rejected what I and others have called “the famous artist entitlement to piracy,” to reaffirm and further clarify Campbell.

The Court reasoned that:

“Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists. Such protection includes the right to prepare derivative works that transform the original. The use of a copyrighted work may nevertheless be fair if, among other things, the use has a purpose and character that is sufficiently distinct from the original. In this case, however, Goldsmith’s photograph of Prince, and AWF’s copying use of the photograph in an image licensed to a special edition magazine devoted to Prince, share substantially the same commercial purpose. AWF has offered no other persuasive justification for its unauthorized use of the photograph.”

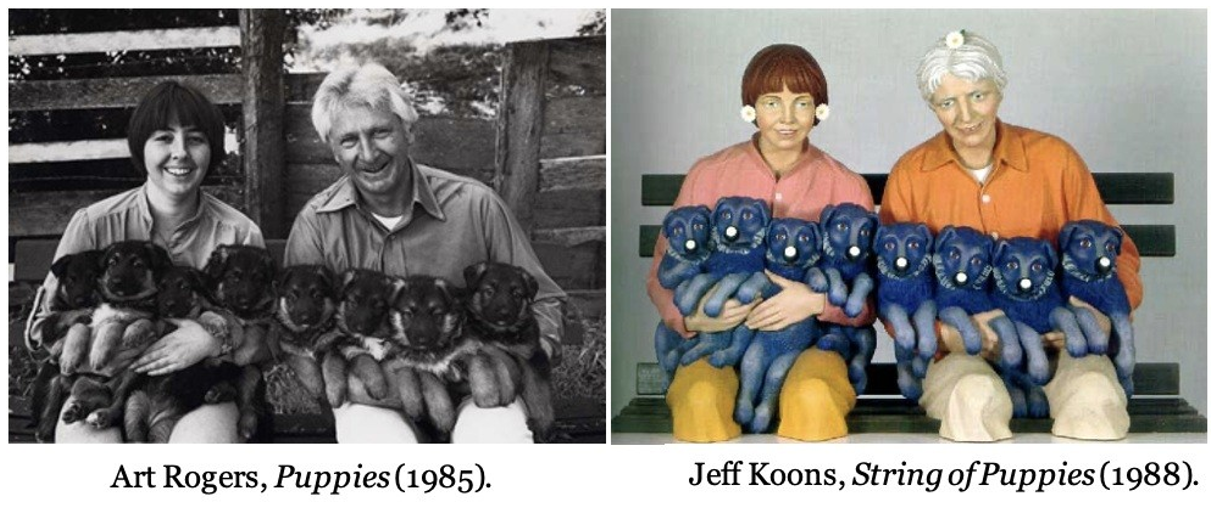

Not since the Second Circuit decision in Rogers v. Koons (1992)— a case involving Jeff Koons’s appropriation of photographer Art Rogers’s work in the sculpture “String of Puppies” — has the art world has been so roiled by a copyright fair use case. In rejecting Koons’s defense based on his right to use photographs by characterizing the images as “facts,” — which are free from copyright protection — to comment on society, the Court stated:

“It is the rule in the Second Circuit that though the satire need not be only of the copied work and may also be a parody of modern society, the copied work must be, at least in part, an object of the parody, otherwise there would be no need to conjure up the original work […] Copies made for commercial or profit-making purposes are presumptively unfair. The crux of the profit/nonprofit distinction is not whether the sole motive of the use is monetary gain but whether the user stands to profit from exploitation of the copyrighted material without paying the customary price.”

I litigated for the artist Faith Ringgold in the case of Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television (BET) in 1997. Faith’s husband Bertie had seen an episode of the TV sitcom Roc. In the last five minutes of the episode, a poster licensed by Ringgold for production by the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, which owned the original “Church Picnic Story Quilt” (1988), appeared on a church wall as set dressing. However, the poster’s copyright text is too small for a television viewer to discern. Ringgold alleged that a poster of her work was used in the set’s decoration without copyright permission by Home Box Office (HBO) and BET. I cautioned that a series of district court precedents had failed to accord proper protection to the use of art in film and, notwithstanding the commercial aspects of the use, that the use did not satisfy the aforementioned factor one of criticism or scholarship. The lower courts had failed to protect visual arts with the same vigilance as music in films, primarily because visual artists

don’t have bodies like the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) or Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) to defend artists’ rights, particularly the financial means to appeal a clearly wrong district court decision. Predictably, we lost in the district court. The district court stated, “[t]he Poster was used as a small part of the set to help portray an African-American church, and the brief nature of the defendant’s use of the Poster bolsters the conclusion that its presence was incidental to the scene,” and that this use did not compete with Ringgold’s sale of the poster. The crux of the profit/nonprofit distinction is not whether the sole motive of the use is monetary gain, but whether the user stands to profit from exploitation of copyrighted material without paying the customary price, with no analysis of the licensing revenue garnered by Ringgold from derivative works. We appealed.

The Second Circuit denied BET’s claim that its use of the poster wasde minimis ( too “trivial” ) for fair use, notwithstanding that the aggregate time in which the poster appeared in the show was about 27 seconds. To this argument, the Court responded that BET’s argument that all it used was the idea of black folks dancing, is to say that we only took the smile of the Mona Lisa. As is relevant here, the Second Circuit, following Campbell, considered the first fair use factor with the preamble illustrations as a “guide … we observe that the defendants’ use of Ringgold’s work to decorate the set for their television episode is not remotely similar to any of the listed categories. In no sense is the defendants’ use ‘transformative’ …” and further “…In the absence of defenses, (i.e. fair use) these exclusive rights ( including the right to license derivative works) normally give a copyright owner the right to seek royalties from others who wish to use the copyrighted work.

BET used Ringgold’s work for precisely the purpose for which it was created — for decoration. Indeed, the poster is the only decorative artwork visible in the church hall scene. Nothing that BET has with the poster “supplant[s]” the original or “adds something new.”

By 2009, however, the concept of transformative use had muddied the waters. The preamble purposes and whether the work was for commercial purposes and the burden placed on the second user had almost disappeared, swallowed up by a transformative use analysis that threatened, in particular, the copyrights of photographers and their right to license derivative works. The watershed which lead to the district court’s analysis in Warhol was anticipated by the flawed analysis in Cariou v. Prince (2013). In 2009, artist Richard Prince was sued by French photographer Patrick Cariou for copyright infringement after his “Canal Zone” paintings incorporated photographs from Cariou’s 2000 book Yes, Rasta. In March 2011, a US district judge ruled — in my view, correctly — against Prince on the basis of Campbell and ordered the defendant to destroy any unsold paintings that borrowed imagery from Cariou. That ruling was largely overturned on appeal a year later, apart from five paintings that were ordered to be reevaluated for claims of fair use. Museums lined up with Prince to argue an apocalyptic vision of artistic creation if Prince could not use Cariou’s work. Professor Amy Adler was paid by Prince’s team and was the source of a new standard embodying the “famous artist exception,” justified as an incentive for creating new work by famous artists with no mention of paying the customary price.

The Second Circuit held that the district court imposed an incorrect legal standard when it concluded that, in order to qualify for a fair use defense, the artist’s work had to comment on the photographer, the photographs, or on aspects of popular culture closely associated with the photographer or the photographs. The Court ruled that 25 of the artworks made fair use of the copyrighted photographs because the artworks presented a new expression, meaning, or message. The artworks were “transformative” because they manifested an entirely different aesthetic from the photographs since the artist’s composition, presentation, scale, color palette, and media were fundamentally different and new compared to the photographs, as was the expressive nature of the artist’s work. Rather astonishingly, the Second Circuit opinion arguably rests in part on the flawed reasoning of the district court in Ringgold, that Richard Prince’s work is not a market substitute for and therefore does not “supersede” the demand for the original. That rationale, which is also echoed in Justice Kagan’s dissent in Warhol, with respect to transformative use is now, practically speaking, in the dustbin, a low point rather than high water mark in the analysis of fair use.

The decision and the process leading to Sotomayor’s opinion are remarkable in many ways. As a constitutional law professor, I always relished reading Supreme Court opinions, but the fascinating repartee between Kagan and Sotomayor isat a level that is unusual in its tone and passion. It is well worth a read even for a nonlegal scholar and aids in providing an understanding of the majority opinion, which easily refutes the doom and gloom predictions of both Justice Kagan and the numerous briefs in support of the Warhol Foundation which undergird Justice Kagan’s analysis. That the Supreme Court failed to give a blanket copyright pass to all appropriation art and artists who create it, does not mean the end of the First Amendment, and incorrect weighting of copyright law to protect and incentivize at the expense of progress in the arts.

So, what is the impact of the decision? I’ll sum it up in five points:

(1) Fair use is a case-by-case analysis. While the Court specifically declines to adopt a bright line rule giving a copyright pass for all appropriation art based on a new message or aesthetic, the Court specifically acknowledges Warhol’s Soup Cans and other works which comment on advertising logos and labels in principle meet the test of fair use. Artists may still claim fair use for the use of logos to comment on consumerism and other aspects of popular culture or other purposes.

(2) Justice Sotomayor’s opinion does not ignore the relevance of the second work’s meaning or expressive value, but the message must comment on the use of the original copyrighted work. Warhol could have done his own portrait of Prince, or paid the customary price; but to use a work, the secondary use must comment on it. Confirming the Second Circuit, the majority opines that judges should not attempt to evaluate the artistic significance of a particular work. Nor does the subjective intent of the user (or the subjective interpretation of a court) determine the purpose of the use. But the meaning of a secondary work, as reasonably can be perceived, should be considered to the extent necessary to determine whether the purpose of the use is distinct from the original; for instance, because the user comments on, criticizes, or provides otherwise unavailable information about the original. Warhol’s recognized influence on modern art and on artists working today will not be chilled by this decision, nor is the First Amendment threatened by the failure of judges to act as art critics to impute new meaning and message to artworks which simply reproduce an existing work for the same purpose as the original.

(3) “Worried about the fate of artists seeking to portray reclining nudes or papal authorities, or authors hoping to build on classic literary themes? Worry not,” the majority opinion reassures us, since comment and criticism on the original iconic work is clear.

(4) The Court does not specifically analyze the other fair use factors and thus makes no finding as to copyright infringement of the other 16 silk screen works, and specifically rejects the hyperbole of the museum community: the Warhol silk screens and portraits can continue to be exhibited in museums.

(5) Given the number of copyright lawyers who opined on behalf of stakeholders on both sides, we can expect, notwithstanding the elegance, simplicity, and clarity of the decision and its consistency with a long line of Supreme Court precedent on fair use, that litigation on fair use will be a legal staple. Several months after the Second Circuit decision, the Supreme Court decided Google v Oracle, technically the first fair use opinion in 25 years; generating a request by the Warhol camp and anti-copyright silicon valley intellectual property scholars and software advocates to invoke the finding that Google’s exact copying of Oracles’s java script transformative and fair use. Neither the Second Circuit nor the Supreme Court found that Google analysis of factor one was inconsistent with its decision that AWF’s license of Goldsmith’s photograph with minor changes for the same purpose was not transformative.” The fact that computer programs are primarily functional makes it difficult to apply traditional copyright concepts in that technological world. That said, stay tuned for how artificial intelligence will play out in the future of copyright. For example, is the act of feeding exact copies of copyrighted artwork to AI software (in order to train it to produce its own artwork later) “transformative” under the first factor?

I understand that rather than being treated as a hero as she should be for defending the rights of artists, Goldsmith has been attacked based on the unwarranted doom and gloom of the dissent. It is difficult to see how this litigation had required 59 friends of the Court brief, about half on each side. This fact no doubt provided added support to the Kagan dissent, which is not based on precedent, but on the art world power structure.

In fact, most, if not all, of Justice Kagan’s arguments are refuted. I particularly like Sotomayor’s response to Kagan about the dire effect on creativity of the majority ruling:

“If AWF must pay Goldsmith to use her creation,” the dissent claims, this will “stifle creativity of every sort,” “thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge,” and “make our world poorer.” These claims will not age well. It will not impoverish our world to require AWF to pay Goldsmith a fraction of the proceeds from its reuse of her copyrighted work. Recall, payments like these are incentives for artists to create original works in the first place. Nor will the Court’s decision, which is consistent with longstanding principles of fair use, snuff out the light of Western civilization, returning us to the Dark Ages of a world without Titian, Shakespeare, or Richard Rodgers.”

Remember: fair use is a case-by-case analysis. If the original work that was taken is recognized, and used by the second user for the same purpose as the original without any specific comment on the first work, the use is probably not transformative under factor one.

Stay tuned for further copyright developments following the decision.