Art world insider Barbara T. Hoffman’s guide to navigating the implications of current developments in art law as they relate to artists, collectors, galleries and museums, as well as a forum for the discussion of the implications of current events at the intersection of art, law, politics, and culture for the art world and beyond.

An art world friend with more than 50,000 thousand followers on Instagram, advised me to stick to writing on art law: that is why people look to you. Admittedly, I have not followed the advice: a focus on politics, culture and the survival of artists, friends and clients in this unprecedented period of political brinkmanship and COVID 19 involves sharing information and strategies for what is literally survival of our institutions, our values, and of course our humor and equanimity in the face of it all. This newsletter refocuses on an area of expertise and passion: the subject of artists, copyright, and the contours of various judicial doctrines implementing or detracting from those protections. The subject is provoked by a webinar in three parts I was invited to present via Zoom in May and June to the American Society of Media Photographers entitled “Know Your Rights, Monetize Your Assets: Copyright and Other Legal Issues for the Professional Photographer.” Since that webinar series, a number of other significant developments involving art, artists, social media, copyright, and fair use make this a timely and important subject for all creatives and those who license creative works.

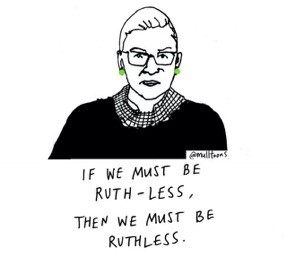

Of course, the newsletter concludes with some humor with some useful information and resources in the middle.

A Social Media Victory in the Courts for Photojournalists

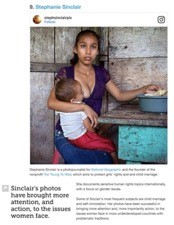

The past few years have seen a plethora of lawsuits brought by professional photographers against news websites alleging that the websites’ use of Instagram’s embedding API to display images originally posted by the photographers on their personal Instagram accounts constitutes copyright infringement. Sinclair v. Ziff Davis, LLC, and Mashable, Inc was one of such cases. In 2016, Mashable republished National Geographic photographer Stephanie Sinclair’s photograph without her consent and permission in an article by embedding her photo from Instagram. In 2018, Judge Kimba Wood dismissed Sinclair’s Second Amended Complaint, finding that Mashable had used Sinclair’s photograph pursuant to a valid sublicense from Instagram, and that using Instagram’s embedding API was not infringement.

In a similar case brought in 2020, McGucken v. Newsweek LLC, a photographer posted on his Instagram account a photograph of an ephemeral lake that had appeared in Death Valley, California. The following day, Newsweek published an article about the ephemeral lake, embedding the photographer’s Instagram post of the lake as part of the article. The photographer sued Newsweek for copyright infringement. In that case, Judge Katherine Polk Failla found on June 4, 2020 that though Instagram’s various terms and policies clearly foresee the possibility of entities such as Newsweek using web embeds to share other users’ content, none of them expressly grants a sublicense to those who embed publicly posted content.

Ars Tecnica, in an article with the headline “Instagram just threw users of its embedding API under the bus,” reported that in answer to an email it sent following Judge Failla’s decision, a company spokesperson for Facebook (which owns Instagram) has stated, on the record, that Instagram’s terms of use do not grant permission to users of its embedding API to display embedded images on their websites without additional permissions from the copyright owners

On June 24, 2020, Judge Wood granted Sinclair’s motion to have the Court reconsider and reverse the motion to dismiss her Second Amended Complaint for copyright infringement. On the basis of Judge Failla’s decision, Judge Wood found insufficient evidence that Instagram exercised its right to grant a sublicense to Mashable.

Judge Wood found that while the platform’s policy might be interpreted to grant API users the right to use the API to embed the public content of other Instagram users, that is not the only interpretation to which that term is susceptible, quoting Judge Failla in McGucken v. Newsweek. The Court then relied on Agence France Press v. Morel, my case involving AFP’s theft of my client Daniel Morel’s iconic photographs of the earthquake in Haiti in 2010 based on false reliance on the Twitter TOS, (the jury awarded him over one million dollars) for the proposition that the platform’s policy terms are not sufficiently clear to warrant dismissal of Sinclair’s claims on a motion to dismiss.

While the good news is that Instagram’s Terms of Service are no longer seen as granting rights to an embedded image, it is still unfortunate that the status of embedding in the Second Circuit remains unclear, with Judge Wood and Judge Failla finding no infringement for embedding, and Judge Katherine Forrest, in my view correctly, finding that embedding itself constitutes copyright infringement (Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, LLC).Goldman is correctly decided and has I have previously argued in another case, the Second Circuit (New York) , should not follow the Silicon valley friendly, Ninth Circuit and such cases like Perfect 10 which find embedding and framing not to interfere with the copyright holder’s right to display/ transmit a work.

FAIR OR FOUL: PROTECTING CELEBRITY ARTISTS AT THE EXPENSE OF A CREATOR’S RIGHTS. ANDY WARHOL FOUNDATION v GOLDSMITH (2nd Cir. 19-2420)

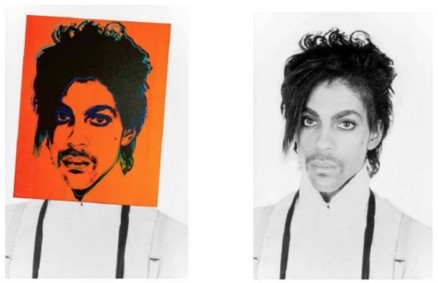

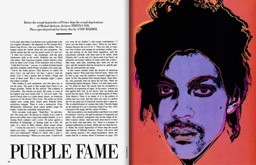

Oral argument in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in the Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith took place on September 15, 2020. In the lower court case (The Andy Warhol Foundation For The Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith et al,) Judge Koeltl of the SDNY, incorrectly in my opinion, decided on a motion for summary judgement (there were no disputes as to the facts), that Andy Warhol’s silk screen images of Prince which copied noted portrait photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s image of Prince, did not constitute copyright infringement. On July 1, 2019, Judge Koeltl ruled that when Andy Warhol copied an unpublished photographic portrait of the late singer Prince, (allegedly provided to him by Vanity Fair as a resource), and created 16 different variations of the unpublished photo, that these were “fair use” and not copyright infringement. Plaintiff, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, immediately praised the decision saying “Warhol is one of the most important artists of the 20th century, and we’re pleased that the court recognized his invaluable contribution to the arts and upheld these works.”

“Fair use” is a statutory affirmative defense to copyright infringement. 17 U.S.C. § 107. “The four factors identified by Congress as especially relevant in determining whether the use was fair are: (1) the purpose and character of the use; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; (4) the effect on the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.” The critical question in determining fair use is whether copyright law’s goal of “prompt[ing] the Progress of Science and useful Arts would be better served by allowing the use than by preventing it.” To make that determination, the Supreme Court has articulated in the case of Campbell v Acuff Rose that one work transforms another when “the new work … adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message. Although transformation is a key factor in fair use analysis under factor one, whether a work is transformative is often a highly contentious topic, more often applied it appears to justify a conclusion, than it is a bright line rule of law. And recently the direction seems to be in the direction of denying to photographers the copyright protection to which their work is entitled, thus, upsetting the delicate balance between the promotion of the artist’s creativity by providing to artists the rewards of their creations and promoting the ability of secondary users to create using freely the seeds of their creation.

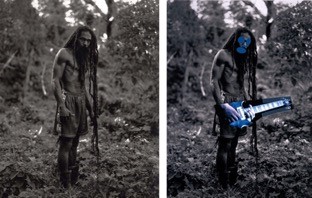

Of course, an artist’s celebrity status is not written into the copyright law under Section 107, the section on fair use. For that misunderstanding, one needs to look at a sharply criticized and debated 2013 Second Circuit decision in the case of Cariou v. Prince, the most recent articulation of the muddled and murky fair use doctrine. Plaintiff Patrick Cariou published Yes Rasta, a book of portraits and landscape photographs taken in Jamaica. Defendant Richard Prince was an appropriation artist who altered and incorporated several of plaintiff’s photographs into a series of paintings and collages called Canal Zone that was exhibited at a gallery and in the gallery’s exhibition catalog. The issue was whether defendant’s appropriation artwork, which incorporated plaintiff’s photographs, must comment on, relate to the historical context of, or critically refer back to the plaintiff’s original work to qualify for a fair use defense. The question was of course raised, because in Acuff, 2 Live Crew did just that.

The Second Circuit found Prince’s uses to be fair. A secondary use does not need to comment on or critique the original in order to be transformative as long as it produces a new message. In this case, while Cariou’s book of 9 ½” x 12” black-and-white photographs depicted the serene natural beauty of Rastafarians and their environment, Prince’s work featured enormous collages on canvas that incorporated color and distorted human forms to create a radically different aesthetic. Therefore, even though Canal Zone did not comment on or critique Yes Rasta, the court still held that it was a transformative fair use of Cariou’s photographs. Whether or not art is transformative depends on how it may “reasonably be perceived” and not on the artist’s intentions.

As a District Court Judge, Koeltl was bound to follow Cariou: “In sum, the Prince Series works are transformative. They ‘have a different character, give [Goldsmith’s] photograph[] a new expression, and employ new aesthetics with creative and communicative results distinct from [Goldsmith’s].’ See Cariou, 714 F.3d at 708. They add something new to the world of art and the public would be deprived of this contribution if the works could not be distributed. The first fair use factor accordingly weighs strongly in AWF’s favor.”

The court also found no evidence that the defendant’s work usurped either the primary or derivative market for the plaintiff’s photographs. Even if a secondary use damages or destroys the market for the original material, it can still be fair use as long as its nature and target audience are different from those of the original.

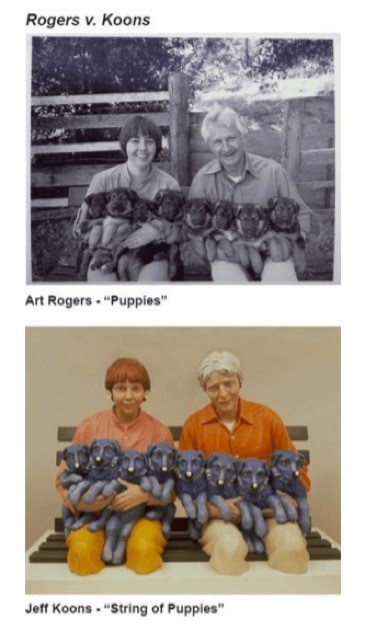

In finding Warhol’s use transformative, the court denies protection to those elements of a photographic portrait that are protected by copyright law, as if the fair use defense to copyright infringement and the concept of celebrity transformative use literally erases “substantial similarity” and fails to appreciate how extensively Warhol’s silkscreen is derivative of and misappropriated protected expression from Lynn Goldsmith’s photographic portrait of Prince. It is perhaps because of the Second Circuit’s decision in 1992 in Rogers v. Koons, finding that protectible elements of originality in a photograph may include “posing the subjects, lighting, angle, selection of film and camera, evoking the desired expression, and almost any other variant involved,” Judge Koeltl did not consider the Warhol Foundation’s argument that the works were not substantially similar. Notwithstanding, the court’s lack of solicitude for such camera-related choices in Goldsmith’s portrait of Prince seemed to erase these copyrightable protected elements to support the finding of transformative use. His analysis of factor one seems to consider photographs as raw material facts or ideas which are not the subject of copyright protection.

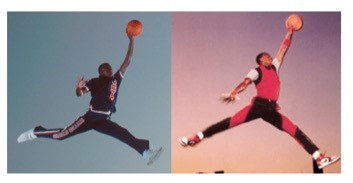

Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc: Photographs Are Imbued with No Less Creativity Than Any Art Form

The idea that “photographs are imbued with no less creativity, depth, and meaning than any other art form, and as such should be entitled to the full protection of copyright law” is an essential concept to consider when examining the scope of copyright protection for a photograph. Notwithstanding, in Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., the Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court’s dismissal of a copyright infringement claim filed by Jacobus Rentmeester (“Rentmeester”) against Nike, Inc. (“Nike”), holding that Nike’s photograph was not “substantially similar” to Rentmeester’s photograph as a matter of law. The Ninth Circuit’s misguided application of copyright law in finding that the works were not “substantially similar” has serious implications for photographers’ development of creative works in the future because that legal conclusion means that there is not copyright infringement even though as in this case, Nike had access to the image. The determination that this iconic pose was the equivalent of an unprotected idea which flows from basketball threatens the ability of photographers to be remunerated through license revenues for their creativity.

In 1984, Rentmeester photographed Michael Jordan (“Jordan”) for an issue of Life Magazine that highlighted athletes who would be competing in the Summer Olympic Games. The photograph featuring Jordan in “an artificial dunk pose inspired by ballet” is revered “by TIME Magazine as one of the most influential images of all time.” In addition to the unique ballet pose, Rentmeester largely orchestrated many of the elements of the photograph, including the camera position, strobe lights, and shutter speed.

Subsequently, Rentmeester and Nike executed a licensing agreement that allowed Nike to use the color transparencies of his photograph. However, Nike violated this agreement when it hired its own photographer to shoot a photograph of Jordan that was “obviously inspired by Rentmeester’s” photograph. Nike’s photograph captured many visually similar elements to the Rentmeester photograph, notably the leaping position towards the basketball hoop and the camera angle. Then, Rentmeester allowed Nike to use its photograph on billboards and posters for two more years for $15,000. In 2015, Rentmeester filed suit for copyright infringement because Nike continued to reproduce the photograph after the original two-year term expired.

The Ninth Circuit held that even though the two photographs are similar, the photographs are not substantially similar because Nike’s photograph displays distinct and creative photographic choices. Additionally, the court reasoned that there was no copyright infringement because Rentmeester cannot prevent other photographers from capturing the idea “of Jordan in a leaping, grand-jete-inspired pose.”

The First, Second, and Eleventh Circuits award copyright protection for a photographer’s “artistic judgment” in contributing “original elements” to a photograph. If the photographs were analyzed in one of these circuits by considering Rentmeester’s creative choices in the “selection and arrangement” of photographic elements, the court would most likely have found that the photographs are substantially similar. Unlike the Ninth Circuit, these circuits would have found that a ballet-inspired pose is both original and protectable under copyright law, and therefore, “substantially similar” as did Judge Koeltl, with some reluctance in Warhol.

An Amicus brief submitted by a group of law professors on the Warhol side, “Brief of Amici Curiae Law Professors in Support of Appellees and Affirmance,” is particularly troublesome in this regard. It states that “Warhol’s Prince Series has similarities with the underlying photograph of Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith, but inspection reveals that the overall aesthetic impression of the Warhol Prince Series is completely different from the Goldsmith photograph. The dramatic divergence in visual rendition makes the two works not substantially similar. Although the district court was correct to grant summary judgment in favor of Warhol, Andy Warhol Found. for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 382 F. Supp. 3d 312, 331 (S.D.N.Y. 2019), traditional infringement analysis is a more fundamental ground on which to decide this case than fair use.”

Their arguments would totally eviscerate copyright protection for photographers, both artistic and photojournalists, effectively depriving one category of creators of the ability to earn a living for the interests of celebrity artists and corporate America. Patrick Cariou and Lynn Goldsmith provide photo documentation and narratives which might not otherwise be told. To deprive them of their licensing revenues from derivative works, display and reproduction is to cut at their means of livelihood and artistic production.

Equally as troublesome is the argument of the Rauschenberg Foundation in the Amicus Curiae brief it submitted on the side of the Warhol Foundation. Rauschenberg himself appropriated, without paying the customary price, the work of photojournalists on the front lines, depriving them of licensing revenue. The Rauschenberg Foundation argues “that two observers may perceive different messages while looking at a secondary work that borrows from an original one. But if one of those observers may reasonably perceive a ‘new expression, meaning, or message’ in the secondary work, the work should be deemed sufficiently ‘transformed’ for fair use.” That is an even bigger stretch than Cariou. The arguments of these two wealthy foundations who state a mission to support artists clearly do not include the photographer or photojournalist amongst the worthy of their support.

Judge Sullivan, sitting by designation at oral argument, asked the right questions. He seemed to understand issues like licensing and the rights of a copyright owner, including the right to control derivative works. Let’s hope this leads to a remand but if not, a rejection, of the broad interpretation of fair use requested by the Warhol Foundation and its supporters and which lurks in the lower court decision balancing of the fair use factors.

Barbara London’s Book and New Podcast

Barbara London, the prescient curator who founded MoMA’s video program, has published with Phaidon, January 22, 2020, Video/Art: The First Fifty Years. The book now in a second printing recounts the artists and events that defined the medium’s first 50 years and is a bible to video as Roselee Goldberg’s Performance Art, also by Phaidon, is to that field.

Not one to rest, Barbara, less than six months after publication, is engaged in a new endeavor to share her abundant knowledge, energy and creativity. She launched an exciting new podcast series, Barbara London Calling, where she portrays “media art as the farthest-reaching, most innovative art of our time—a kind of art, and artist, that plays an essential role in the study and understanding of contemporary art in general.”

Her podcast is worth the listen and a complement to the book. I look forward to future episodes, which, like Performance Art, was almost a Cinderella, until through efforts of Barbara, the majesty and influence of the medium has been recognized.

Her most recent episode features Cao Fei, an “artist who works across film, digital media, photography, sculpture, installation and performance. She has a keen interest in documenting the social impact of technological developments over the last two decades. Cao Fei is interested in how the virtual world contradicts and coincides with reality, resulting in something ambiguous and complex. Her starting point is China and how people, especially young people, navigate the rapidly changing social and technological landscape.”

This is an exceptional listen, and a complement to the book. I look forward to future episodes about media art, which, like Performance Art, was almost a Cinderella, until through the efforts of Barbara, the majesty and influence of the medium has been recognized. You can find the Cao Fei episode at https://www.barbaralondon.net/cao-fei/ . I encourage you to find other episodes and learn more about the podcast series at https://www.barbaralondon.net/barbara-london-calling-podcast/ .

Howardena Pindell at The Shed

In some exciting news, Howardena Pindell’s latest exhibit Rope/Fire/Water will open at the Shed on October 16, 2020. In her first solo exhibition at The Shed, Pindell presents her first video in twenty-five years, an extraordinary and thought-provoking piece “examining the violent, historical trauma of racism in America and the therapeutic power of artistic creation.” Timed tickets are available free through October 31. https://theshed.org/program/143-howardena-pindell-rope-fire-water

To learn more about Howardena and her remarkable life and artistry, I wholeheartedly encourage you to read the interview she did with the New York Times in July, which discusses her 1990 work “Scapegoat.” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/24/t-magazine/howardena-pindell.html.

For Your Consideration…

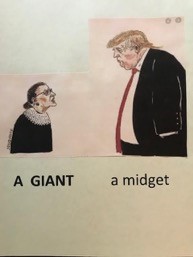

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry, I do know after the “debate,” I intend to vote early and in person. Vote and encourage everybody you know to vote in person and early!!!